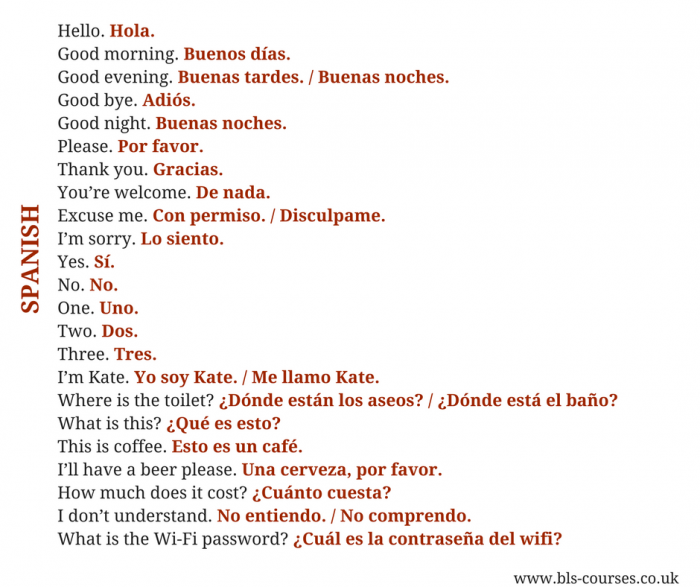

When you learn a new language, you may have to learn to use a new alphabet or writing system too. An alphabet is a set of letters that is used to write a language. The letters represent sounds in the spoken language. Other types of writing systems, that do not use alphabets, use characters that represent syllables or words rather than sounds. A few of the languages you can learn at BLS (Arabic, Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, Russian) use an alphabet other than the Roman alphabet (the one English is written in) or a different writing system. Even some of the languages that do use the Roman alphabet have characters that are not used in English (e.g. Czech, French, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Spanish).[1]

Learning a new alphabet or writing system is not something we are necessarily used to doing (except if you specialise in maths, music or computing, perhaps), but it can be done. These tips below should give you some pointers on how to go about learning and remembering a new alphabet or writing system. It may only take a few hours or days to learn the system, actually – but then of course you need to keep practising it to make sure it sticks in your mind! It is a good idea to try and learn the alphabet or writing system as soon as you can as it will make things easier as you go on. It is harder to unlearn a substitute system you are using, like transliterating the sounds with an English alphabet that it is to learn the writing system of the language you are learning from the word ‘go’. The language will make more sense to you as a whole as well if you learn the alphabet that it is written in.

Learn how the writing system works

First things first: familiarize yourself with how the writing system works. What is different about it? Does it use syllables or consonants and vowels? Are the vowels written above the letters? Does it connect its letters? Do you read it horizontally, vertically, left to right or right to left? This helps you get a feel for the writing system or alphabet and means there shouldn’t be too many surprises when you are learning what the words are.

Associate letter shapes with familiar objects

Try to associate the shapes of letters with familiar objects: some letters may look like letters or numerals in your own alphabet, others may remind you of animals, objects or people. You can use the word association technique we looked at in a previous post to help you think of stories to go with these animals or people to help you remember the sound/word the letter or character represents. A good example from this webpage is how to memorise the Japanese character の, which is pronounced “no”. The character looks like a “do not” sign, which you can associate with the phrase “no smoking”, which gives you the “no” sound represented by the character. This blog post recommends doing this for every character and abandoning ‘romanisation’ (trying to transliterate sounds into the Roman alphabet) altogether. Actually, in Chinese and Japanese, some of the characters already do this for you, because they developed from trying to represent objects visually anyway. Sometimes you can recognise what they are, such as the symbol for moon in Mandarin Chinese, 月亮, part of which, 月, is used to write the month of the year (一月 January, 二月 February, 三 月 March, and so on). The concept of months arose with the cycle of moon phases, so this makes sense.

Also try to see whether letters are similar to each other; this can mean that they have a similar sound. For example, the sound ‘ga’ in Japanese is represented by the symbol が, which looks like the symbol for ‘ka’(か) with two apostrophes added to it.

Learn a few letters or characters a time

Try to learn the letters or symbols a few at time rather than all in one go. Try to learn them according to a system as well. For example, in Japanese, the symbols can be grouped by initial consonant sound, e.g. か(ka), き(ki), く(ku), け(ke), こ(ko) or final vowel sound e.g. か(ka), さ(sa), た(ta), な(na), は(ha), ま(ma), や(ya), ら(ra), わ(wa) and so on. You can use flash cards or another system to look at the letters, symbols or words repeatedly and remember them. Try to learn at least one word that uses each letter or character you have learned (this takes longer with a writing system than with an alphabet!).

You should be careful of letters that look like letters in the alphabet you already use but are ‘false friends’, i.e. they look like letters you already know but do not have the same sound. For example, in Russian the following letters look like English letters but are pronounced differently: B = [v], H = [n], C = [s] and P = [r]. As an example, the Russian word ‘PECTOPAH’ means ‘restaurant’ and can be transliterated as RESTORAN. This can be the case when you learn languages that do use the Roman alphabet too, where the same letters have different sounds. Have a look at these Italian words as an example: the ‘z’ in ‘zaino’ is pronounced ‘dz’ (‘dzaino’), ‘gli’ is pronounced a bit like ‘lyi’ and the ‘c’ in ‘cena’ is pronounced a bt like ‘ch’ in ‘cheese’ (‘tʃena’), which is not what you might expect from how those letters are pronounced in English.

Write the letters or characters out a hundred times

It really helps you to memorise the letters or characters if you write them out by hand. Trying to memorise them by looking at them in a book or on a computer screen will not be as effective as if you write them down. This is because writing engages your brain in a more active way than reading does. Practice writing the letters as often as possible. If you find it helpful to learn them by following a pattern, write them down according to that pattern. Learning the standard way to write the letters: i.e. the shape, direction and order of strokes, will help you to memorise them and help you to write them legibly. If you can find teaching materials that children use to learn to write at school, that will help a lot. If the language you are learning uses special paper to teach people to write on, try to get hold of that. For example, Chinese languages use writing sheets with boxes and grid lines to help you keep the characters to a uniform size and shape. If you can, take a calligraphy or writing class. This will help you improve your handwriting and get used to other people’s handwriting and computer fonts. Getting used to people’s handwriting is useful even if you are not learning a different alphabet as people form letters in different ways in different countries. Here is an article about how French people learn to write, for example.

Read anything you can get your hands on

Read texts written in the new alphabet as often as you can. Even if you don’t know all the letters or characters yet, you will be able to make out some of the words and to guess the others. Look out for people’s names, place names and loan words from your own language as these can be easy to recognise. Label things around your home or office in the new alphabet. This will help you recognise key words and phrases.

At first you may have to sound out letters individually before being able to decipher the words. Later on, you will be able to recognise words by their shapes and will only need to sound out the letters of unfamiliar words. You probably went through the same process when learning to read your native language. Even writing systems such with Chinese and Japanese characters can be learnt by breaking them down into parts. Try to read aloud in your new alphabet as often as you can as this will help you get used to the sounds the letters or characters represent.

Online material and apps

There are lots of tips on how to learn new alphabets or writing systems on the internet, such as this forum. You can find exercises to help you learn too. There are also several apps specifically for learning and practicing alphabets, and you can even find less common languages there too.

I hope you enjoy learning a new alphabet or writing system and feel proud of your achievement!

[1] E.g. á, à, ä, â, ą, ǎ, ć, ç, é, è, ë, ê, ę, î, ì, ï, ll, ł, ñ, ň, ô, ò, ǒ, ö, ř, ś, ß, ť, û, ù, ü, ú, ǔ, ů, ý, ż, ź, ž.

Written by Suzannah Young